What should pollsters do about undecided voters?

Patrick Flynn

26 August 2022

Back in February, pollsters Opinium changed their methodology for measuring UK voting intention, leading to a debate among Twitter’s psephological community (both professional and amateur) as to its likely efficacy.

The company’s head of political polling, Chris Curtis, outlined all the changes in a Twitter thread, with the major alteration being the way in which they handled undecided voters. Like other polling companies, Opinium previously excluded undecided voters from their sample and did not make any further adjustments to the remaining respondents.

With the new methodology, the remaining respondents are reweighted to be representative of the electorate likely to vote on election day. In simple terms, if 25% of 2019 Conservative voters were undecided, the remaining 75% would be ‘weighted up’ to account for that undecided quarter.

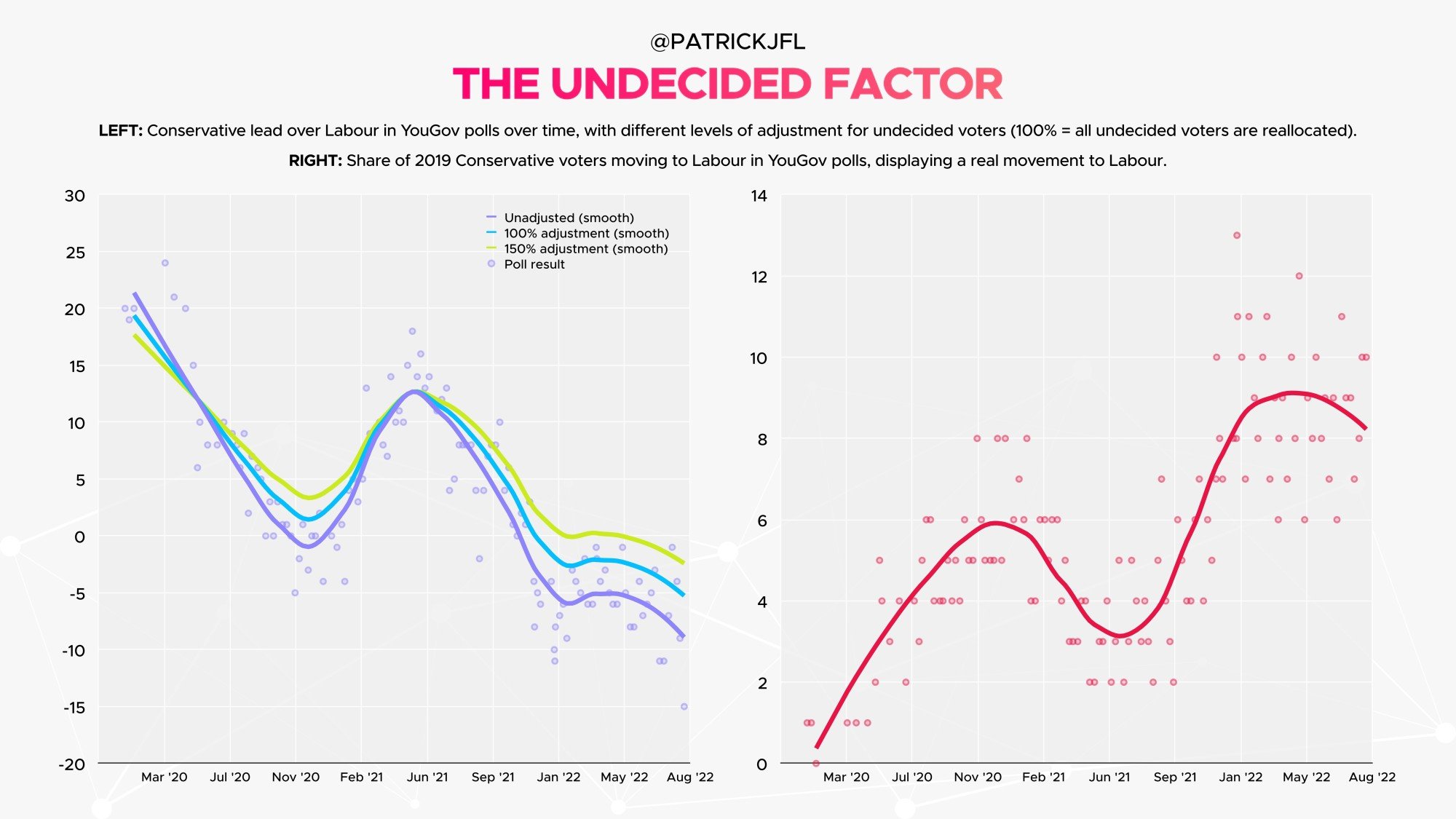

The changes have seen Opinium posting smaller Labour leads and more stable results than some other pollsters. In the six months before February, the average change in their headline lead from poll-to-poll was 2.86% (0.40 points higher than an average of Redfield & Wilton, SavantaComRes and YouGov). In the six months since, that figure has more than halved to 1.36% (0.95 points lower than the average).

To me, the new methodology seems reasonable. The purpose of UK voting intention polls is to gauge how voters would behave in an election held imminently, and that’s what public consumers of polls want to know. Adjusting the weights so the sample matches the demographics of those who would likely turn out in an election serves this purpose more effectively than simply assuming that all the undecided voters two years out wouldn’t participate if the election were held tomorrow.

The key question, though, is whether the new methodology will improve Opinium’s fortunes. It’s all well and good debating its merits or faults in theory, but how does it fare in practice? This is what I set out to research. By analysing historical polls from YouGov (a strong-performing pollster with a wealth of crosstabs available), I compared the headline poll leads with an adjusted figure I arrived at by reallocating undecided voters based on their past vote to match the voting intention of those who stated a party.

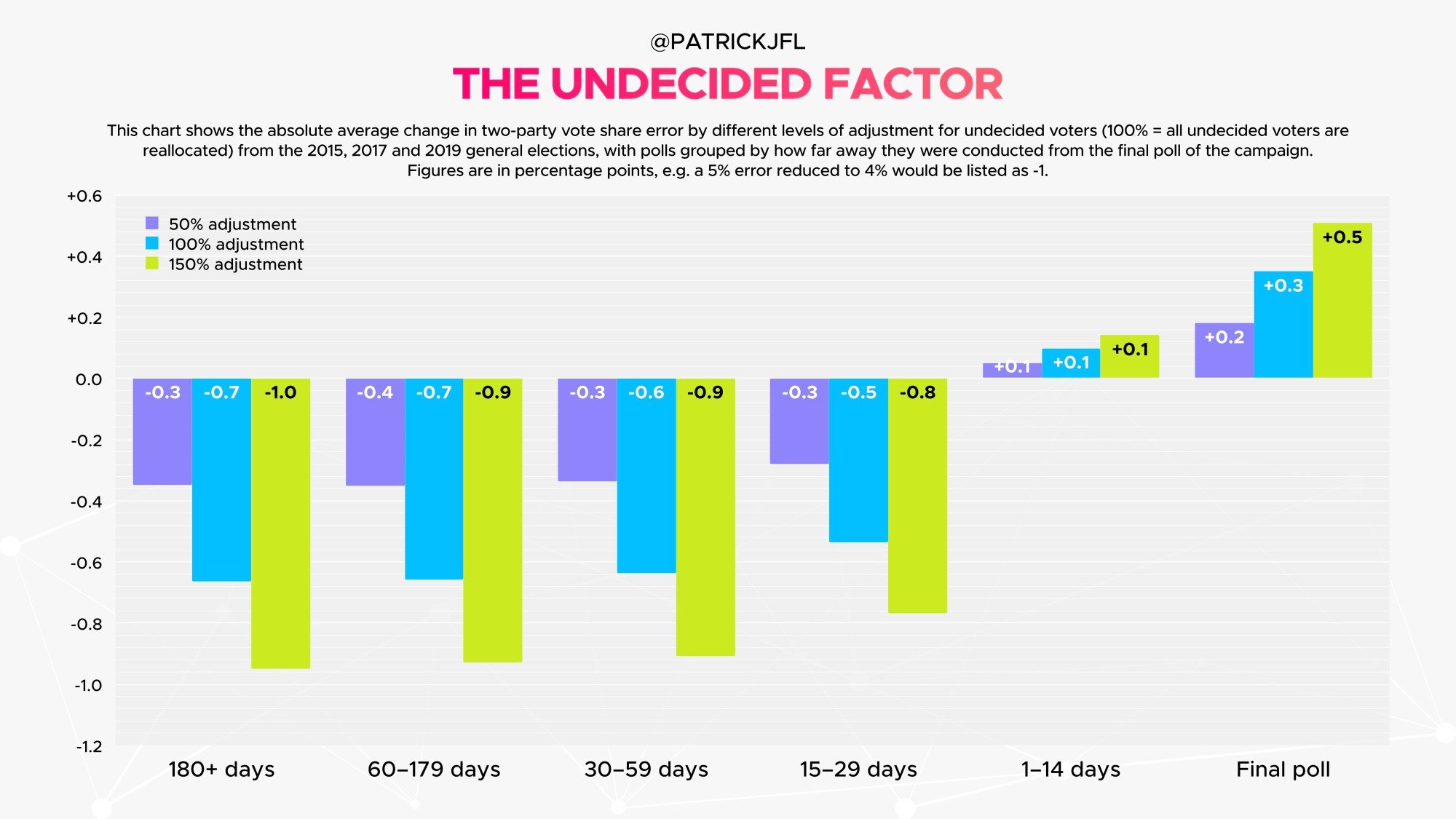

The results were clear. When comparing the adjusted polls with the subsequent election result, polling error was reduced in all three parliaments between 2010 and 2019, with the average RMSE (root-mean-square error) reduced by 8.3%.

Furthermore, there is evidence that accounting for self-predicted turnout alongside undecided voters could reduce overall error even further (there is a relatively strong correlation between the share of undecided voters in each party’s previous electorate and the share who say they are certain to vote, suggesting that a party’s base may be further squeezed in some polls through the application of turnout scales).

However, YouGov’s publicly available data on this metric only goes back as far as 2016, so this is difficult to prove. Given the aforementioned correlation, however, we could instead try and use a proxy to test this extra amendment by, for example, adjusting ‘don’t knows’ by 150% instead of 100%. Though this is only experimental and would need to be tested with actual turnout weights, the RMSE was reduced even further, with a total reduction of 11.6%.

At this stage, eagle-eyed poll watchers will note that in the 2017 election campaign, YouGov made a similar adjustment and ended up snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. In their final poll, the methodology was modified, and a near-perfect 3-point Conservative lead turned into a 7-point one. The actual change seemed rather arbitrary, with ‘don’t knows who were 8 out of 10 or more likely to vote reallocated using their 2015 vote’. YouGov’s reasons for doing this are still contested, but that debate is not relevant here.

So why, if the reallocation of undecided voters apparently works so well, did a similar attempt to do so fail in 2017? The answer is pretty simple: the reallocation only works during midterm polls.

The further out from an election we are, the better the adjusted numbers perform compared to the headline figure. Once we get into the late stages of an election campaign, that advantage disappears. This makes sense when you think about it — many undecided voters two years out from an election will (empirically) make up their mind by the time of the vote, whereas undecided voters two days out will be much less likely to turn out than the former group, so they should not be treated in the same way.

Looking at current polls, much has been made of a recent YouGov survey which gave Labour a 15-point lead, the largest the company has recorded since 2013. Around a third of this lead, however, comes purely from the undecided gap between 2019 voters of each party. Once don’t knows have been accounted for, YouGov end up broadly in line with Opinium’s most recent Labour +8 poll.

In summary, the data suggests that Opinium are on the right track with their new polling methodology, though I hope undecided voters will be treated differently when it comes to the final few polls of the election campaign. That election is potentially over two years away, however. At where we are in the electoral cycle, the evidence is clear, and pollsters need not be undecided about the undecided any longer. Will any of them follow Opinium’s lead?

Patrick Flynn

26 August 2022