Jeremy Corbyn: could the former Labour Leader win as an independent?

Patrick Flynn

30 March 2023

After Jeremy Corbyn was blocked from standing as the Labour Party’s general election candidate in Islington North, speculation now turns to whether the former Labour leader will stand as an independent in the seat that he has represented for 40 years and, crucially, whether he could go on to win.

I probably go against the grain somewhat in saying that Corbyn would stand a decent chance of victory if he ends up standing as an independent, and here’s why.

This wouldn’t be the first time that Corbyn has upset the odds – let’s not forget that he was the 200/1 rank outsider at the start of the 2015 leadership election that he went on to win. Even when he was challenged for the leadership in 2016, he traded as short as 1.25 to leave the role that year (he ended up fighting two general elections after that). I make this point in jest, but there almost seems to be an inversely proportional relationship between Corbyn’s early prospects and his subsequent results.

A political outsider, Corbyn appears to be in his comfort zone as an underdog and that is where he has ended up surpassing expectations (whereas we saw how 2019 went when Labour were early favourites to win that election post-2017).

Let’s start with the downsides of his potential candidacy. Firstly, it’s true that independent candidates don’t usually fare very well in general elections – even longstanding MPs who stand against their own party. In addition, no current Labour MPs would be allowed to campaign for Corbyn, lest they risk being expelled from the party. Those factors are drawbacks for the former Labour leader’s prospects.

I have also read comments about the supposed lack of ‘personal vote’ for Corbyn in Islington North by weighing up his constituency results with nearby MPs in comparable seats, but I think these rudimentary analyses ought to be ignored. In reality, there is no easy way to measure a candidate’s personal vote outside of an election in which they stand as an independent.

Rough metrics used to calculate supposed personal vote, such as how much an MP’s vote share diverged from their party’s during their time in office, bear no relationship to how independent candidates fare at elections (the R-squared value for that metric was 0.019). Even if we were able to perfectly assess how Corbyn compared to an average Labour candidate, that still doesn’t tell us a whole lot about how an election would go for one key reason: we wouldn’t know what proportion of Labour voters (which made up 64% of the constituency in 2019) would back Corbyn as an independent. This demographic is the most important because a former Labour voter is worth twice as much to Corbyn, increasing his vote count by one while reducing his nearest rival’s by the same amount.

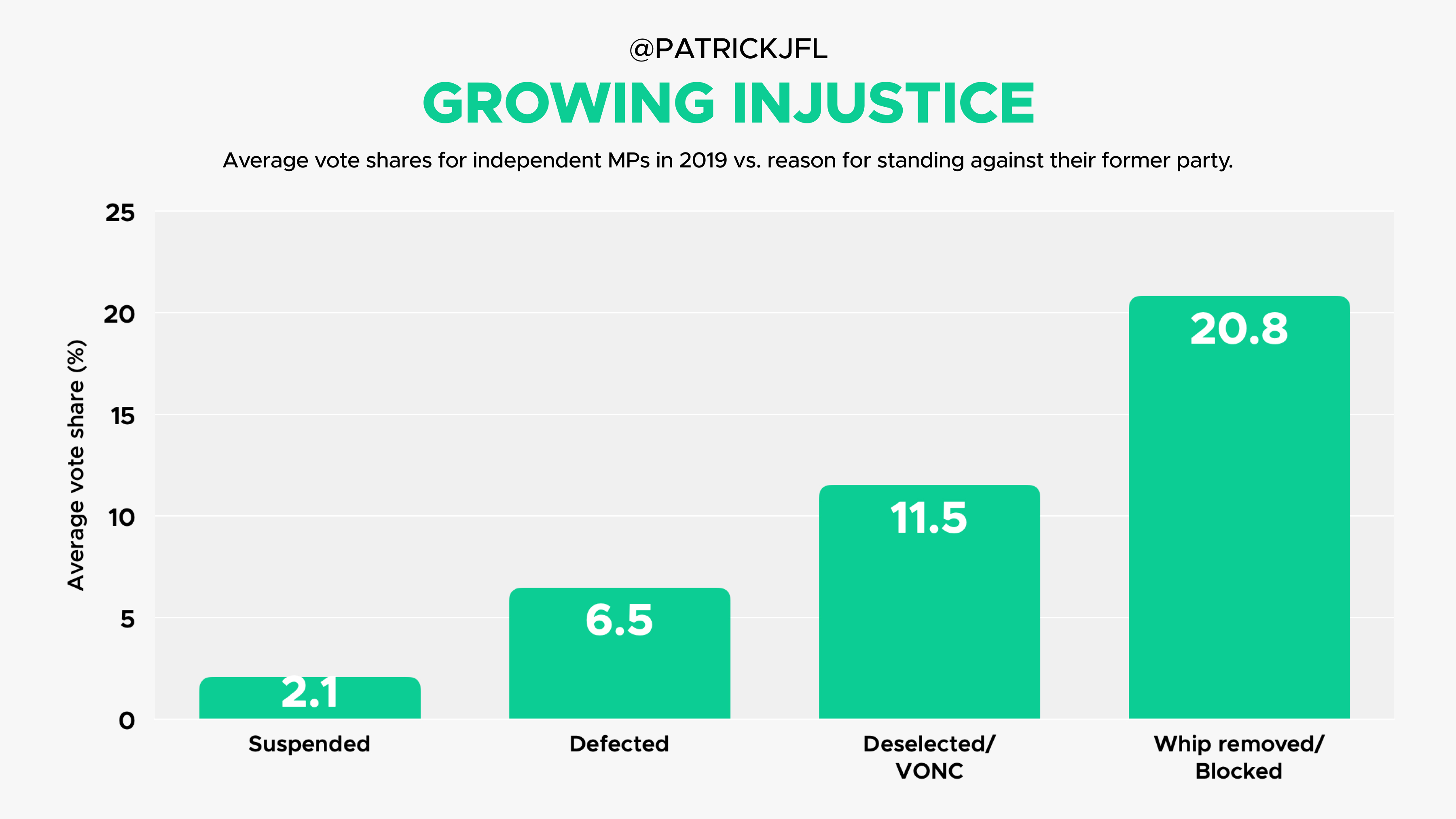

Let’s look back to 2019 to get some data on how he might actually fare. During that turbulent time, there were an outsized number of MPs standing against their former party in the same constituency – 11 in total. The reasons they couldn’t stand under their usual banner fall into four categories: suspended as a party member for breaking rules, willingly defected, deselected/lost a confidence vote in their constituency, or had the party whip removed/blocked from standing. These groups are listed in ascending order of what we might consider to be levels of perceived injustice, which also correlates with how each fared.

Very few voters would be forgiving of an MP who was suspended from their party for sexual misconduct, for example, whereas many might be more sympathetic to a serving MP who was blocked from standing when local party members wanted them. Caveats, of course, apply given the small sample size, but the two suspended MPs received an average vote share of 2.1%; the three who willingly defected got 6.5%; those who lost or would have lost a confidence vote averaged 11.5%; and those who were blocked from standing managed a pretty respectable 20.8% (though none of the MPs went on to win).

There also appears to be a correlation between each candidate’s national profile (measured by YouGov data) and the vote share they received (again, caveats apply). Seemingly, the more people that knew of the candidate nationally, the higher their vote share, a pattern which emerges even within the subgroups.

Among the MPs who were blocked, for example, Dominic Grieve had the highest profile (54% fame according to YouGov) and received the highest vote share, whereas Anne Milton (19% fame) was the most unknown and went on to receive the lowest vote share. It’s easy to understand why: MPs with a higher national profile will be more likely to pull in donations and draw in volunteers from different constituencies to help out on their campaign.

This is where things get interesting for Islington North because Corbyn falls into the most favourable categories on both of these metrics. He was blocked from standing despite remaining a Labour member, and he also has a very high profile – much higher than any of the 11 MPs in question – being one of the most famous politicians in Britain with 95% name recognition.

It becomes difficult to assess how Corbyn might do because his national profile lies so far outside the range of the 2019 data. The amount of media attention on the constituency and the number of volunteers who will end up campaigning for him will be vastly greater than any of those 11.

The best historical comparison with Corbyn’s situation might not be any constituency election, then, but Ken Livingstone’s independent London mayoral run in 2000. The parallels are pretty strong: a long-standing left-winger with a high profile in London is prevented by the national party from winning a selection he would have won under the normal rules.

Livingstone ultimately went on to win 39% of the first-round vote as an independent and was subsequently elected Mayor of London. Corbyn will be hoping to replicate this success with a grassroots campaign focused on his record as a constituency MP and the sense of injustice around his candidature being blocked.

There are also some important differences, though. While I will let everyone pass their own judgement on some of Livingstone’s more recent comments which got him expelled from Labour, I don’t think he generated the same levels of antipathy in 2000 that Corbyn does in 2023. Somewhere in the Livingstone range of 35–40% may end up being the base rate for Corbyn, but would be no guarantee of victory if his opposition is united against him in a way it wasn’t for Livingstone.

Corbyn’s local party being fully behind him is a major boost, though. For starters, it means Labour’s candidate will in all likelihood not be local or well-known in the constituency, which helps Corbyn to juxtapose his long-standing record as a deeply-embedded constituency MP against a potentially parachuted Labour candidate. Secondly, while voter targeting data is only supposed to be held by the local party, let’s just say I wouldn’t be surprised if that data ended up with Corbyn’s campaign in some form or another.

Independent victories in British politics are pretty infrequent given the nature of the voting system and tend to require a specific combination of factors. Though it will be an uphill struggle, Corbyn may just end up being one of those rare cases.

Patrick Flynn

30 March 2023