Can we rely on political odds?

Matthew Shaddick

26 July 2022

Stephen Bush, in the FT, has written a short blog: Why we cannot rely on bookmakers' odds. I thought I'd pen a response.

I'm certainly not going to argue that you should only "follow the money" or that betting markets can provide a crystal ball view of the future. However imperfect the political markets may be, I still think they are generally the best way of assessing the probabilities of outcomes, whether sporting or otherwise. Of course Smarkets isn't really a bookmaker in the traditional sense but here we're mostly talking about the "markets" which are usually driven by what is happening on exchanges like ours.

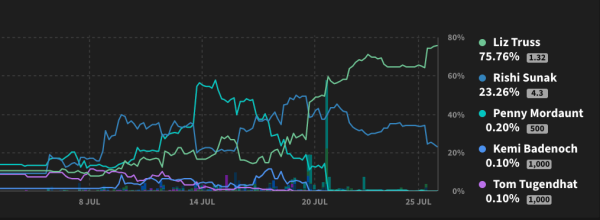

Let's take Stephen's points in order. He highlights a chart showing how volatile the odds have been in the Tory party leadership race so far. Luckily, at Smarkets we have these sorts of time series graphs available to anyone at anytime - here's how this one looks so far.

I don't think these sorts of wild fluctuations really prove anything about how predictive the markets are. These events are best seen as analogous to an in-play sports market, albeit stretched over a much longer time. New information is coming in all of the time - MPs' ballot results, debate reactions, polls of party members and so on. Does the market sometimes over-react to those new data points? Yes, I think that does happen a lot. Still, if you looked at a similar graph for an in-play horse race or a tennis match or whatever, you would also find some lines bouncing about all over the place. That does not mean that sports betting markets are poor predictors; on the contrary, the markets for major sports are hugely efficient. If you looked at all of the tennis players given a 30% chance of winning they do, in fact, win 30% of the time (or very close).

Still, political betting is not like that. We don't have thousands of Tory party leadership elections to analyse, model and compare odds to reality. For that reason, it's pretty hard to confidently say how good the betting markets are at generating probabilities. Stephen cites an academic paper which claims that polls are better than markets at predicting elections. Even if that were true for the particular category they looked at (US presidential elections before 2008) political betting encompasses a lot more than national votes. It's also worth saying that the political betting landscape has changed a lot since 2008. There are many more platforms operating and some of these markets are much more liquid now. It's hard to be sure of the growth, but I'd be fairly confident that the amount of money wagered worldwide on the 2020 US presidential election might have been 10x that in 2008, and probably a lot more.

Stephen points out that some traders are simply anticipating price movements and taking advantage of those rather than forecasting the final result. There definitely is some of that going on, but experience tells me that it is at the margins, and if that activity ever pushed the odds for a particular event happening to an unrealistic level, market forces would tend to move them back. He also points out that Tom Tugendhat's odds were above Liz Truss's at one point in the campaign - which they were briefly on 8 July the day after Tugendhat launched his campaign and five days before the first ballot. That might seem silly in retrospect, but I'm afraid pointing out odds that seem stupid after the event does not impress me very much, unless you have a betting slip showing that you took advantage. As it happens, Stephen is one of the last people you could criticise for that sort of thing as he is one of the few political journalists who takes the trouble to make clear and measurable predictions in advance.

There are many other inefficiencies one could exploit - bookmakers leaving up stale prices, getting information before the rest of the market and so on. That doesn't require any particular insight into the world of politics but otherwise, beating the political markets is not that easy, which it should be if the odds were poor forecasts. If, for instance, one really could just say "polls are more accurate than odds" then it would be trivially easy in the long run just to rely on polls and win money on the markets. The incentives and penalties on offer will (in theory) self-correct any flaws in the market.

Admittedly, there are times when even very liquid markets seem to be overwhelmed by hunches and poorly informed money - I was arguing that was happening during the 2020 US presidential race when Trump's odds seemed completely detached from the polls. Turned out that the public money was actually very close to the mark and Trump did indeed outperform the polling averages. Luckily for every "shrewd" politics punter in the world, Biden squeaked to victory nonetheless.

Matthew Shaddick

26 July 2022